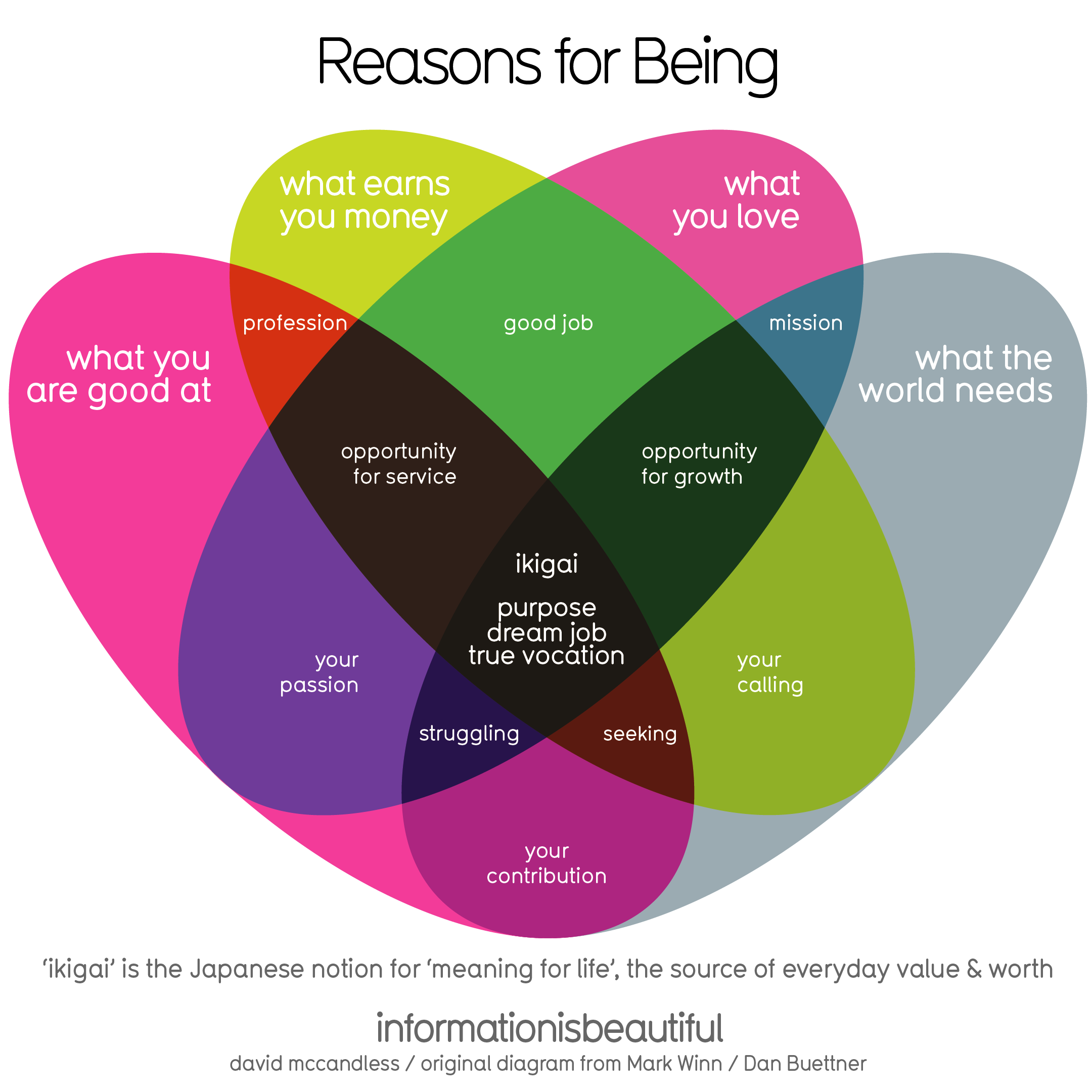

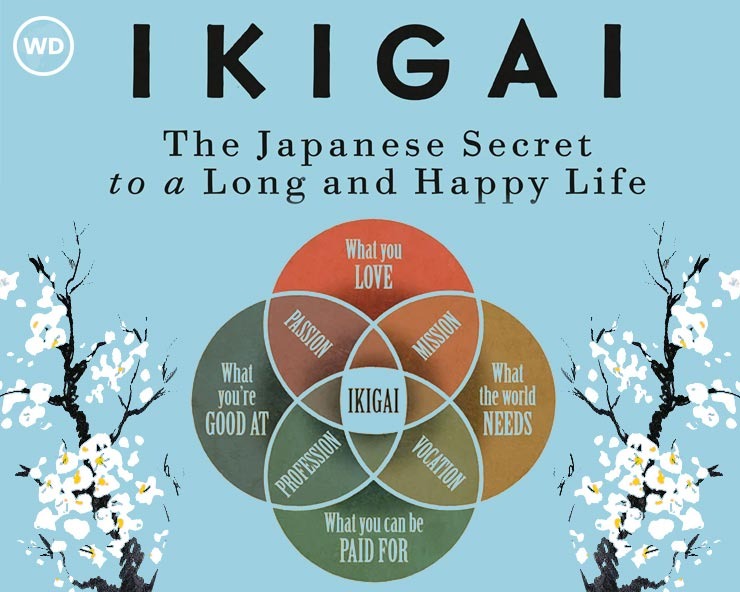

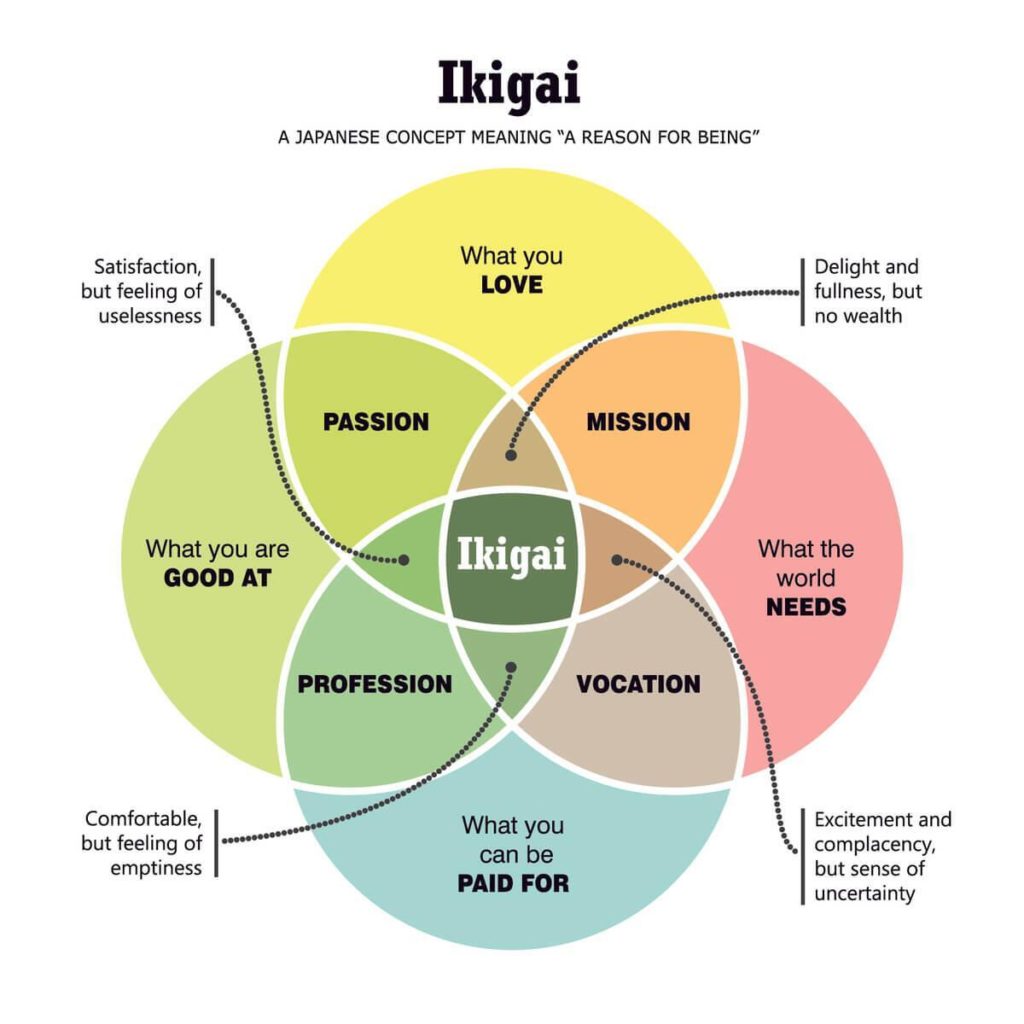

Iikigai is rooted in finding the intersection between what one loves, what one is good at, what the world needs, and what one can be paid for. It involves elements of passion, vocation, mission, and profession. In storytelling, an anti-hero is a character who possesses some qualities or behaviors that are typically associated with antagonists or villains, but they are still the central character in the story. They often have morally ambiguous or flawed characteristics, and their motivations may differ from traditional heroes.

Ikigai is often associated with realizing a sense of contentment, fulfillment, and balance in one’s life. Psychologist Katsuya Inoue has further expanded on the concept of ikigai by emphasizing two aspects: the sources or objects that bring value or meaning to life, and the feeling that one’s life has value or meaning because of the existence of those sources or objects.

Inoue categorizes ikigai into three directions from a social perspective: social ikigai, non-social ikigai, and anti-social ikigai.

Social ikigai refers to activities or pursuits that are accepted by society, such as volunteerism or participation in social circles. Non-social ikigai refers to sources of meaning or objects that are not directly related to society, but still provide personal fulfillment, such as faith or self-discipline. Anti-social ikigai refers to motivations or pursuits that may stem from negative emotions, such as a desire to hate, seek revenge, or harm others.

These categorizations highlight the different dimensions of ikigai and how it can manifest in various ways for individuals. It’s important to note that while anti-social ikigai may exist, the overall concept of ikigai focuses on finding positive meaning, purpose, and fulfillment in life.

Ikigai is a concept rooted in Japanese culture that refers to the reason for being, or the sense of purpose and fulfillment in life. While it shares some similarities with Zen philosophies and the Western concept of raison d’être, ikigai has its unique characteristics.

In Zen philosophies, the emphasis is on mindfulness, presence in the moment, and attaining enlightenment through meditation and self-reflection. The path to finding one’s purpose and fulfillment often involves letting go of attachments, desires, and ego. In contrast, ikigai is more focused on finding the intersection between what one loves, what one is good at, what the world needs, and what one can be paid for. It involves elements of passion, vocation, mission, and profession.

The concept of anti-social ikigai, as described earlier, does align with the journey of a flawed character seeking balance and redemption through the course of a story. Anti-heroes may start off with negative motivations or engage in morally questionable actions, but as the story progresses, they often undergo transformation, learning, and growth. Their journey involves finding a sense of purpose and fulfillment despite their flaws.

These flawed characters often provide a more complex and realistic portrayal of human nature, challenging traditional notions of heroes and villains. They can be intriguing and relatable because they reflect the intricacies and contradictions of the human experience.

Examples of popular anti-heroes in literature and media include characters like Walter White from “Breaking Bad,” Tony Soprano from “The Sopranos,” or Severus Snape from the Harry Potter series. These characters are not purely heroic, but their journeys and struggles captivate audiences and offer unique perspectives on personal growth and redemption.

To create the antihero character, is it best to use raison d’être of existentialism to develop motivation of the individual’s reason or purpose for existence emphasizing finding a meaningful purpose in life and aligning one’s actions and endeavors with that purpose? Or better to create anti-hero character is it better to base the lies the character believes on ikigai system of finding meaning and purpose via spontaneity and a sense of being in touch with one’s inner self?

Creating an antihero character can be a fascinating process because antiheroes are typically complex, operating in the grey area between traditional heroism and villainy. They possess traits that can make them relatable to the audience while also acting in ways that might not be considered traditionally moral or ethical. When considering the antihero’s raison d’être or the lies they believe, both existentialism and the concept of ikigai can serve as compelling foundations.

Existentialism: This philosophy revolves around the idea that individuals are free and responsible for their own development through acts of the will. By using existentialism, you can develop an antihero who navigates a world lacking inherent meaning, thus negotiating their own moral compass. This can be a strong way to craft a character whose motivations are self-determined, deeply personal, and often in conflict with societal norms. Their actions can be aimed at defining their own purpose or rebelling against what they perceive as an absurd or unjust world.

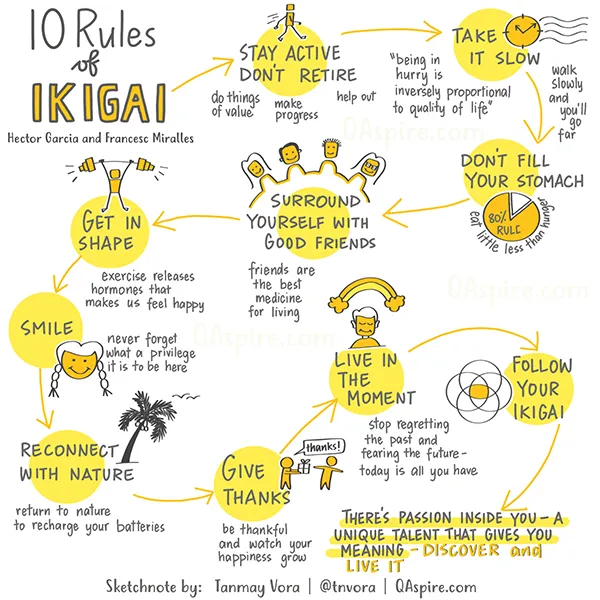

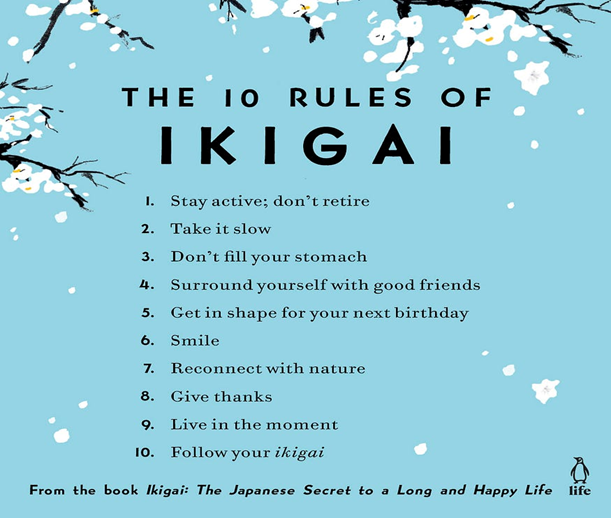

Ikigai: This Japanese concept refers to something that gives a person a sense of purpose, a reason for living. Ikigai is often visualized at the intersection of what you love, what you are good at, what the world needs, and what you can be paid for. An antihero who is motivated by their interpretation of ikigai may believe in a specific mission or ideal that they feel compelled to achieve, which aligns with their skills and passions but might not align with societal expectations. This could lead to actions that are at odds with the world around them because their inner sense of purpose does not match the reality they face.

Employing existentialism in character development could result in an antihero who is focused on their personal choice, freedom, and responsibility, often wrestling with moral ambiguity and the consequences of their actions. In contrast, a character driven by their unique interpretation of ikigai might have a more defined sense of purpose, while still potentially embodying an antihero’s edge due to the personal nature of what they find meaningful versus what society expects of them.

Ultimately, the choice between existentialism and ikigai when developing an antihero might boil down to the specific narrative you wish to tell, the cultural context you are working within, and how you want the audience to connect with the character.

Both philosophies offer rich soil for character growth and conflict, which are essential elements in the journey of any antihero. The best approach could even be a blend of both — an antihero whose inner sense of purpose (ikigai) leads them to existential choices and conflicts that define their narrative arc.